The following morning the

work began with my first real task as a WWOOFer.

I was keen, and determined to make a good job of whatever was in store for me.

My challenge for the morning? To clear rocks from an area of garden. It didn’t

sound too taxing. Heavy duty gloves at the ready, Caleb and I went to the area

in question and were faced with an almost perpendicular slope, where pebbles

and rocks and boulders all seemed to grow out of the dusty ground. I never

discovered quite what Pierre was planning to do with this land, but to me it

seemed too unforgiving to plant on yet too steep to build on. Still, a job was

a job, and ours was not to reason why. As we lugged hunk after hunk of stone up

the slope, Caleb made a Sisyphus-related joke. I don’t think I had ever met

anyone outside of my family who could allude to an essay by Camus with quite

such nonchalance. And yet he was right: like Sisyphus, that deceitful Greek

king who was punished by the powers of Mount Olympus, we were rolling stones up

a hill for no apparent reason, only to start all over again once we reached the

top. Il faut imaginer Sisyphe heureux:

you had to believe that Sisyphus was happy, otherwise his life must have been

unbearably depressing and pointless. I didn’t have to imagine myself happy,

though. The sun was beginning to warm my back, and I could feel the contours of

the rocks through the scratchy lining of the too-big gloves, and I was farming

in France!

How could I possibly not be happy?

Half an hour before each mealtime

it was left to me to go down the garden to pick enough salad for a hungry

family. Fontchouette had three gardens: a high garden by the road where

potatoes, roots, onions and a few salads were being cultivated; a middle garden

close to the house, filled with strawberries, apricots, herbs and swathes of

lettuce, and a massive lower garden comprising a greenhouse sheltering tomatoes

and yet more lettuce, a pond, and rows and rows of sugarsnap peas and raspberry

canes, leeks, courgettes, apple trees, pear trees, baby quince saplings,

aubergines, peppers and more that I didn’t recognise.

Thankfully the lettuce that was

ready for consumption whilst I was a guest was growing in the middle garden, so

I didn’t have so far to walk. I learned to cut them so that the remaining

lettuces stood the best chance of growing larger, as well as to check the

leaves for the orangey eggs of a certain species of fly who liked to reside

there. To ensure that all bug-related gunk was removed, I was expected to wash

each leaf individually before drying them and tearing them up to eat. I was

shown how to make an accompanying vinaigrette by shaking olive oil, mustard and

vinegar together in a jam jar, and it was down to me to make this fresh each

mealtime, too.

Food at Fontchouette was almost

entirely home-grown or home-made, either by Anne-Marie and Pierre or by friends

who lived nearby. Lunch was invariably fresh salad, a hunk of chewy, delicious

bread made by a woman at Lamastre market which may or may not have been made

with rye flour, home-made, hand-churned butter, and cheese. Usually the cheese

was a strong, rich comté made by Pierre,

although for variation they bought cheeses from friends once a week, perhaps a

soft, crumbling white goat, or a smelly but delicately veined blue. It was at Fontchouette

that I eventually learned to like blue cheese, to appreciate its salty, earthy,

creamy tang as a gastronomic experience rather than fearing it as a by-product

of decomposition. The farmers laughed at me at first, so tentative in my tiny

mouthfuls. But I did so want to like the taste, and eventually my aversion

subsided and I found myself choosing Roquefort for the pleasure of it. All that

remained on my list of foods to learn to like were oysters, having ticked off

mushrooms and eggs earlier that year. I was fairly sure I could get through

life without liking oysters.

The same spread was offered for the

main meal of the day, but with the addition of something hot. Often this was

fresh pasta from the smiling young man I had seen when I arrived at market. I

would have boiled the pasta, but Anne-Marie had the strange custom of

slathering it in olive oil and roasting it. The spaghetti turned into

wonderfully crispy bootlace chips, and the stuffed ravioli were to die for:

moist and flavoursome on the inside, the bottom layer of pasta still soft and

yielding on the teeth and the top layer baked to a crispy shell. Another

offering was beef, as Pierre owned a herd of cows. Mostly they were to provide

milk for the butter and cheese, but inevitably they were destined for the plate,

meatballs in home-grown tomato ragoût. Breakfast was, once again, based

on bread and butter, but this time the bread was toasted and accompanied by

local honey, or home-made jam or marmalade, and home-pressed apple juice.

After each meal it was my job to do

the washing up and to wipe down the table. My shoulders ached slightly at the

end of each session at the sink with a stiffness deep between the blades, and I

wondered why they had chosen to build the work surface so low; I was about the

same height as both Anne-Marie and Pierre, and I couldn’t fathom how they

didn’t suffer equally from hunching over the dishes. Or maybe that was

precisely why they got their WWOOFers

to do the work for them! It was interesting to do the washing up in a house

with no hot water. Mostly the plates only needed rinsing, but when food had

been cooked with oil, the residue was difficult to shift and took a lot of

perseverance and still the crockery didn’t feel quite clean. Thankfully the

sink was in front of a window, so whilst my hands began to resemble prunes, I

had the chance to enjoy the view.

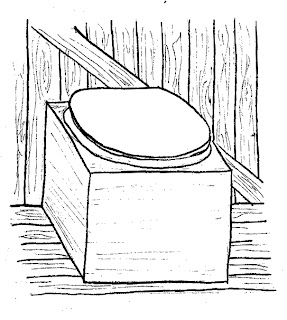

Another place with a stunning view

was the outside toilet. In a three-sided wooden cubicle a stone’s throw away

from the house – the one that I had spotted when I first arrived – a makeshift

toilet had been built over a deep hole. For the sake of comfort, a standard

toilet seat had been fitted over the drop; it was all quite civilised. When I

had first been told that, in the interests of saving water, I should use the

outside toilet during the daytime, I had had a moment of panic. Memories of

family holidays to France

flooded my mind, and particularly memories of the facilities at French service

stations. I had never been able to use them, no matter how desperate I had

been. Squatty bogs, we used to call

them. Standing up just seemed so wrong. What if it went on my feet! I resolved

to exercise my pelvic floor muscles and hang on until dark when it was

permissible to use the inside toilet under the stairs, with its books on

mulching and medicinal plants and the accompanying tubes of herbal toothpaste. So

my relief at finding a conventional toilet seat was immense, even if the flush

had been replaced by a bucket of sawdust.

It was still a touch

difficult to relax though. Shorts down and feeling rather vulnerable, I had two

issues. The first was that there was no engaged

sign; I listened with constant paranoia for scampering feet in the dust. The

second was that there was no fourth side to the cubicle. I was, effectively, on

view to the whole of the valley. The fact that if anyone were to be able to see

me in enough detail to know what I was doing they would have to have a pair of

binoculars trained on the spot didn’t particularly put me at ease: the

possibility existed. Still, it was quite a treat to have half of France spread

before me as I sat there, like a monarch surveying her queendom from the

throne.

No comments:

Post a Comment